HK Film Archive to present "Revisiting the New Wave" (with photos)

******************************************************************

The opening film is the HKFA's restored version of "The Secret" (1979), which will premiere on March 24 at the Grand Theatre of the Hong Kong Cultural Centre. The restored version is 90 minutes long, much closer to its original release than the 85-minute version that has been circulating for years. "The Secret" will also be screened with other films at the HKFA Cinema from March 25 to May 14. The HKFA will organise six free seminars to be conducted in Cantonese with speakers including directors Ann Hui, Chan Wing-chiu, Lau Shing-hon and Peter Yung; film editors Mary Stephen and Wong Yee-shun; and film researchers Law Kar, Winnie Fu, Lau Yam, Sam Ho and Ng Chun-hung.

The New Wave was not an organised undertaking. "Jumping Ash" (1976), co-directed by Leong Po-chih and Josephine Siao Fong-fong, was among the precursors of the New Wave, and embodies many attributes of the movement which broke new ground in local crime movies. Yim Ho's "The Extras" (1978), made amidst the surge of the New Wave, is closer in style to a mainstream film, poking fun at the absurdities in the film industry through physical gags and jocular romps. Tsui Hark's first feature film "The Butterfly Murders" (1979), a hybrid of wuxia, suspense and science fiction, is a defining work of the New Wave.

The wuxia genre is a staple of Hong Kong mainstream cinema. New Wave director Patrick Tam reacted against it with his film debut, "The Sword" (1980), questioning the tenets of wuxia films without abandoning the genre.

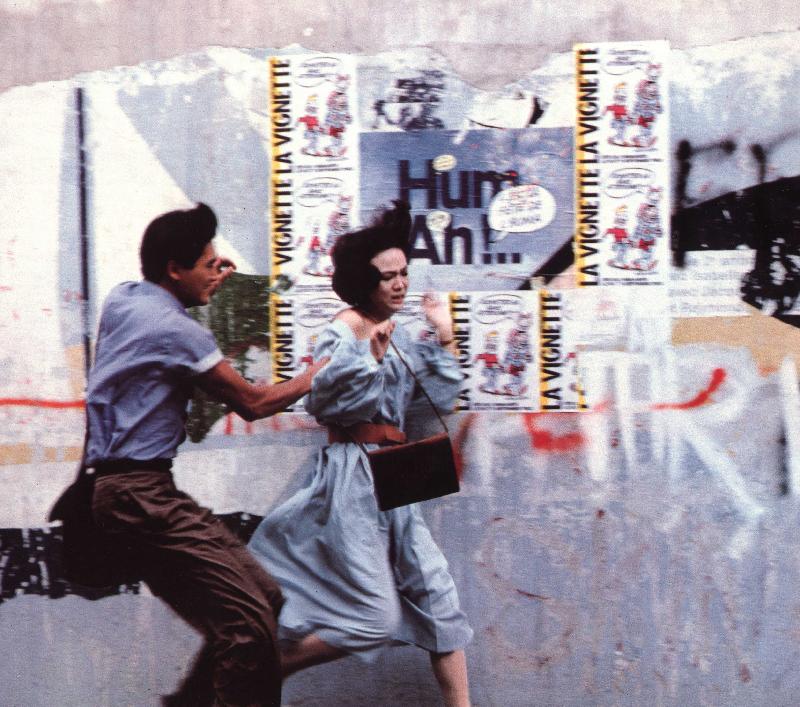

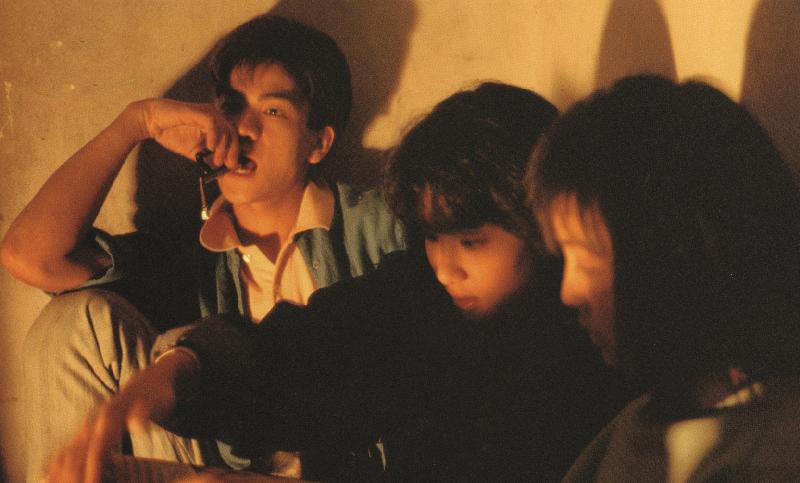

"Dangerous Encounter - 1st Kind" (1980), another New Wave work by Tsui Hark, depicts the director's social critique with violence through the anti-social behaviour of three youngsters. Terry Tong's "Coolie Killer" (1982), imbued with revenge and death, turned the handgun into a symbol of killer sentiments and brotherhood for the many Hong Kong films that followed.

Crime film was also a favourite vehicle for New Wave filmmakers to explore moral issues. Alex Cheung's "Cops and Robbers" (1979) is about a youngster who fails in police recruitment and becomes a psycho killer. Peter Yung's "The System" (1979) depicts with intense realism the ambivalence in the relations between gangsters and the Police.

Sexual desire and jealousy was once taboo in early Hong Kong cinema, but that wasn't the case in the New Wave. Based on a true murder case, Ann Hui's debut feature "The Secret" tells a suspenseful and horrific love triangle tragedy in a non-linear narrative structure. Lau Shing-hon's "House of the Lute" (1980) explicitly depicts the sexual desire of and power struggle between an old man and his young wife.

Young maidens were no longer symbols of purity in the New Wave cinema. Choi Kai-kwong's "Teenage Dreamers" (1982) is about four schoolgirls who are mischievous and playful. David Lai in "Lonely Fifteen" (1982) portrays the loneliness and loss of girls kicked out from school.

Horror films in the New Wave mixed tradition with modernity, paving the way for Hong Kong cinema's genre-blending horror renaissance later. Ann Hui's uproarious horror comedy "The Spooky Bunch" (1980) sets its story in a Cantonese opera milieu while incorporating supernatural folk tales. Taking inspirations from East and West, Dennis Yu's "The Imp" (1981) displays traits of Hollywood horror films, creating chills and fear through visual effects.

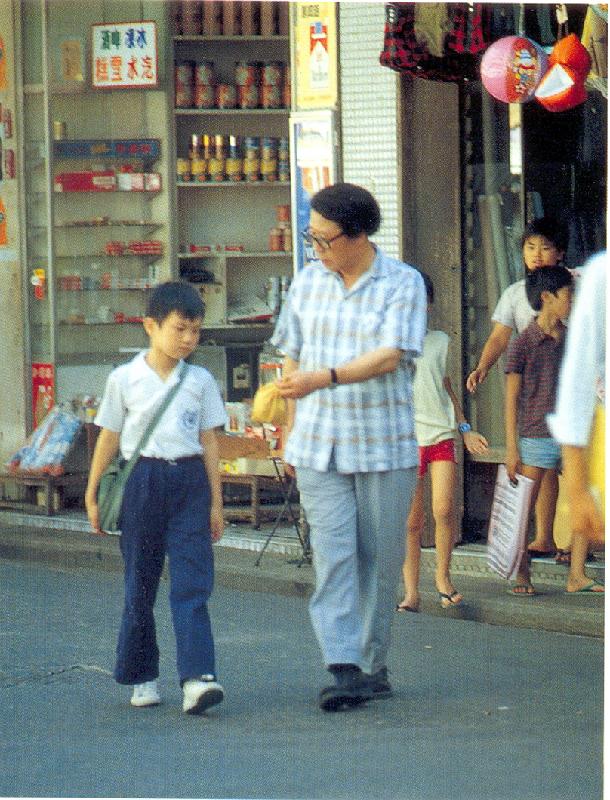

Traditional family values was a ubiquitous topic in early cinematic works, but the New Wave filmmakers had their own definitions of family. Rachel Zen's "Cream Soda & Milk" (1981) follows the encounter of a pair of siblings after their parents divorced through which to examine family issues and the predicament faced by the underprivileged in society. Allen Fong's "Father and Son" (1981) portrays the dilemma between a son's dream and his father's expectations in a social-realist style which deeply touched audiences.

Riding on the surge of the New Wave, a second generation of filmmakers entered the scene in the following years. Tony Au instilled "The Last Affair" (1983) with aesthetic aspirations, spinning a tangled web of romance in Paris. Eddie Fong's period epic "An Amorous Woman of Tang Dynasty" (1984) is meticulously crafted in terms of the script and cinematography. "The Illegal Immigrant" (1985) is the first instalment of Mabel Cheung's trilogy of diaspora stories exploring the topic of migration. In stark contrast to the gritty realism of New Wave works, Stanley Kwan's "Women" (1985) depicts female sensibilities with plenty of delicacy and subtlety. Angie Chan's "My Name Ain't Suzie" (1985) offers a realistic and non-exploitative portrayal of a bar girl working in a red light district. Lawrence Lau's "Gangs" (1988) probes the tragic fate of youth delinquents, exposing the brutality of the gangster world with documentary style. Clara Law's "The Other 1/2 & the Other 1/2" (1988) mixes romance and politics with a light touch.

In addition, selected works of film editors Wong Yee-shun and Mary Stephen will be shown in the programme. Wong is a sought-after editor who worked on numerous New Wave projects, including "China Behind" (1974), "The Servant" (1979) and "Homecoming" (1984). Stephen, who was born and raised in Hong Kong, started her career in Europe under the influence of the French New Wave director Éric Rohmer. Her editing in shorts like "Labyrinthe" (1973), "A Very Easy Death" (1975) and "Vision from the Edge: Breyten Breytenbach Painting the Lines" (1998) and features like "The Aviator's Wife" (1981), "Autumn Tale" (1998), "Umbrella..." (2007), "Gitmek: My Marlon and Brando" (2008), "The Drunkard" (2010) and "Majority" (2010) offer interesting comparisons with the editing styles common in Hong Kong films from the same periods.

"An Amorous Woman of Tang Dynasty" and "Majority" are classified as Category III, so only persons aged 18 and above will be admitted. "China Behind" and "The Drunkard" are in Mandarin and Cantonese; "Vision from the Edge: Breyten Breytenbach Painting the Lines" is in English; "The Aviator's Wife" and "Autumn Tale" are in French; "Umbrella..." is in Mandarin; "Gitmek: My Marlon and Brando" is in English, Kurdish and Turkish; "Majority" is in Turkish; "Labyrinthe" and "A Very Easy Death" are without dialogue and other films are in Cantonese. "The Butterfly Murders", "Coolie Killer", "The System", "The Imp", "Cream Soda & Milk" and "Father and Son" are without subtitles; "Vision from the Edge: Breyten Breytenbach Painting the Lines", "The Aviator's Wife" , "Autumn Tale", "Gitmek: My Marlon and Brando" and "Majority" are with English subtitles; and other films are with Chinese and English subtitles.

Tickets priced at $45 are now available at URBTIX (www.urbtix.hk). For credit card telephone bookings, please call 2111 5999. For programme details, please visit www.lcsd.gov.hk/CE/CulturalService/HKFA/en_US/web/hkfa/programmesandexhibitions/rnw/index.html, or call 2739 2139.

Ends/Friday, February 24, 2017

Issued at HKT 17:42

Issued at HKT 17:42

NNNN