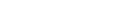

CJ's speech at Ceremonial Opening of the Legal Year 2017 (with photos)

**********************************************************************

The following is the full text of the speech delivered by the Chief Justice of the Court of Final Appeal, Mr Geoffrey Ma Tao-li, at the Ceremonial Opening of the Legal Year 2017 today (January 9):

Secretary for Justice, Chairman of the Bar, President of the Law Society, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen,

On behalf of the Judiciary, I extend a warm welcome to everyone to this year's Opening of the Legal Year. This is the only occasion when the Secretary for Justice, the Law Society, the Bar and I gather together to give our views on the law in Hong Kong. It is an important occasion for me to give my views, where appropriate to do so, on legal matters that are of significance to the community. It is also important that the Secretary for Justice as the principal legal adviser to the Government, the Hong Kong Bar Association and the Law Society as guardians of the law speak on these matters. The importance lies in helping the community better to understand the concept of law. The Judiciary of course has an important part to play in the rule of law in Hong Kong and in the practical manifestation of the rule of law – another name for the operation of the law in practice is the administration of justice. Though crucial the role of the Judiciary, it is not the only relevant institution which has a stake in its advancement. The Government also plays an important role in upholding the rule of law, as do the Bar and the Law Society. In fact, understanding and implementing the rule of law applies to every member of the community and to all institutions within it.

The purpose of the law is to facilitate the functioning of a society – all the more so if it is a complex one like Hong Kong – and to achieve a sense of mutual respect and harmony. This is inherent in the concept of law in society and is implicit in the Basic Law, which is the starting point of any discussion about the law in Hong Kong.

Many people – I among them – have over the years advocated the simple notion that the law means a respect for not only individual rights and interests, but a respect for the rights and interests of other people as well. This is perhaps a useful definition of what a community means. It certainly underlies much of the courts' approach in dealing with in particular public law cases where often different interests will pull in different directions.

This community approach (respect not just of individual rights and interests but respect for everyone's rights and interests) is to be found in the Basic Law:

1. Article 4 (one of the General Principles of the Basic Law in Chapter I) refers to the responsibility of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) as a whole safeguarding the rights and freedoms of all residents as well as other persons in Hong Kong. The reference to the HKSAR is a reference to everyone and every institution here.

2. Chapter III is headed "Fundamental Rights and Duties of the Residents". The reference to residents is a reference to Hong Kong residents. There are set out in this Chapter nineteen Articles. All but one of these Articles set out rights. There is however one provision that sets out a duty on residents. Article 42 states that Hong Kong residents and other persons in Hong Kong shall have the obligation to abide by the laws in Hong Kong. Such laws include of course the laws which give other people established rights and liberties.

3. Among such rights is the important right to equality found in Article 25 of the Basic Law: All Hong Kong residents shall be equal before the law. In other words, in the application of the law in Hong Kong, the law has to be equally applied; everyone's rights and interests, for example, have to be respected. The promise of equality is repeated as the very first Article and again in Article 22 in the Hong Kong Bill of Rights. The Hong Kong Bill of Rights represents the statutory implementation of those rights contained in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which is in force by reason of Article 39 of the Basic Law. The Bill of Rights is contained in the Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance Cap. 383.

It is necessary for this what I have called the community approach to rights and interests to be firmly borne in mind as the relevant context when considering aspects of the work of our courts. The work of the courts in Hong Kong is not only in the public law cases which have lately been in the public eye. High profile cases in fact form very much the minority of the cases undertaken by the courts. The vast majority of the cases heard by our judges, covering areas such as crime, family law, commercial law, real property, personal injuries law and other areas, represent the everyday work of our courts.

Nevertheless, it is in the relatively high profile public law cases where the community approach is best exemplified. It is common in these types of case, usually in the form of applications for judicial review, for many interests – and more often than not different types of public interest – to clash with one another. Often, individuals or groups will be asserting their own rights or interests. There have been many examples of this handled by the courts over the years: cases involving the freedom of speech, the freedom of demonstration, freedom of marriage, social welfare, elections. Every year, there are important public law cases which engage the public curiosity or which cause controversy, but more important, these are cases which enable the community to see the rule of law at work and to test the confidence which the public will have in the rule of law. Perennial questions are then asked in relation to the Judiciary:

1. How do the courts and our judges approach their responsibilities; and

2. does our Judiciary live up to its ultimate responsibility of being one of the principal guardians of the rule of law?

This past year has again seen the Hong Kong courts deal with important cases in public law. Many have been high profile ones. The outcomes of those cases have at least provoked much discussion; sometimes the reactions have been loud. At times, some people and groups from various sectors have voiced criticism of the courts simply because of outcomes to cases not to their liking. Admittedly, courts and judges are not and ought not to be immune to criticism. I fully accept the right of people to comment on the work of the courts, but of course hope that such comments whether in criticism or even praise, should be informed and measured.

An understanding of the approach of the courts is important in this discussion. The basic starting point is a facet I have already highlighted – the concept that all are equal before the law. Many take for granted the impressive statue representing justice standing at the top of the front facade of the Court of Final Appeal. This is the statue of the ancient Greek goddess Themis (in Roman mythology, she is named Justitia). Themis is blind‑folded and holds in one hand the scales of justice, a sword in the other. These are symbols of the administration of justice, which are often taken for granted – just look at the number of legal institutions around the world using Themis to represent justice. However, the significance of these symbols of justice bears repetition from time to time in case this is overlooked in any discussion about the law.

The blindfold represents the approach of the courts in ignoring the identity of the parties who appear in them. No person or institution has any added advantage or correspondingly disadvantage in the courts by reason of who they are or what they represent. This is of course the concept of equality which I have already emphasised. That no person gains an advantage before the courts by reason only of status is easy to appreciate. What is, however, often not quite as well appreciated is that no person should suffer any disadvantage in the eyes of the law by reason of who they are or what they represent either.

Over the past year or so, I have sometimes received complaints from members of the public criticising the courts for the way they have dealt with certain cases. Dissatisfaction is expressed in the courts either not convicting persons of crimes or even where there were convictions, in imposing what are seen to be light, inadequate punishments. Correspondingly, dissatisfaction is also expressed when the courts have convicted or imposed what are seen to be heavy punishments. Whatever motivated these criticisms or comments, it is crucial to bear in mind the approach of the courts. In highly charged or high profile cases, all parties are treated in exactly the same way by the courts as in any other type of case. There is no added value or distinctions. Accordingly, legal principle and legal procedures apply in the same way. Thus, in a criminal case, a defendant will only be convicted if on the available evidence the prosecution proves the case beyond a reasonable doubt. If a conviction results, then any sentence imposed will be determined according to standard and well known sentencing principles. There is no discount or increase to reflect the personal identity of the accused. And where there is any perceived error in the conviction or acquittal, or in any sentence imposed or not imposed, the legal system under which we operate in Hong Kong has a system of appeals going up to the Court of Final Appeal.

The scales of justice held in the right hand of Themis reflect the concept of fairness. And in terms of what I have earlier described as the community approach, it represents the balancing exercise which the courts sometimes have to undertake when faced with different points of view. Weighing different factors on the scales to arrive at a balanced view is not confined to those high profile cases I have mentioned. They exist in the day to day work of our courts. In sentencing, for example, different factors are weighed on the scales: the crime itself, the criminal record of the accused, the age of the accused, the element of deterrence in the public interest and other factors. In public law cases, the value and importance of individual rights have sometimes to be seen against wider community interests, in other words other people's rights and interests. The scales will balance giving more, sometimes less, weight to certain factors. This is where the skill and professionalism of the judge becomes critical.

The role of judges in the administration of justice is key. It is a critical role because of the constitutional duty thrust on our judges to exercise judicial power. The Basic Law uses the term "independent judicial power" in three articles. The exercise of judicial power means the power to give binding and enforceable adjudications on legal disputes. This includes, for example, the power to impose criminal penalties (including imprisonment) in criminal cases and to make orders with financial consequences in civil cases. In the public law sphere, the power exists in the courts even to strike down legislation or executive acts if they are shown to have been made in violation of constitutional principles. These important powers of the court are represented by the sword in Themis' left hand.

The constitutional duty and responsibility on all judges can at times be an onerous one. There is pressure on our judges, but this is not pressure from outside sources or persons. Hong Kong's judiciary is an independent one which handles cases strictly and only in accordance with the law and the spirit of the law. The pressure, rather, stems of course from the heavy workload faced everyday by our judges. But more than this, the real pressure is for judges to come up with the right outcome. There is pressure in determining guilt or innocence, in the adjudication of complex commercial disputes and, in public law cases to reach a just and proper balance between legitimate interests. There is also pressure in arriving at the correct decisions which one knows have important and far reaching consequences. It has often been emphasised by many people, my predecessor and myself included, that the courts only determine the legal questions and only consider the legal merits of the cases before them. This is true but of course it is also to be recognised that the decisions of the courts will at times have serious political, economic or social repercussions.

From the point of view of the community and the courts, it becomes extremely important that the quality of the Judiciary remains of the highest possible standard. This has always been one of the main objectives for me as Chief Justice. Notwithstanding the recruitment difficulties we have for the past few years experienced particularly at the level of the Court of First Instance of the High Court, the maintenance of high standards in the Judiciary cannot be compromised. It remains the case that, speaking as the head of the Judiciary, I would rather there be a shortage of judges rather than to compromise on quality.

The Basic Law states that judges shall be chosen on the basis of their judicial and professional qualities. This does not mean just legal ability and experience (although these qualities are obviously included); it also emphasises the quality of a commitment to the community in the discharge of a judge's constitutional duty. This is an important reason for busy and successful legal practitioners in wishing to join the Judiciary. As one local newspaper recently highlighted, there is a significant difference between earnings in the private sector and the earnings (even including benefits) of judges. Given this, one of the main reasons for successful practitioners to become judges, and for some I would say this may really be the only reason for joining the Judiciary, is to serve the community and also to give something back to society. This is demonstrated by the willingness to take a substantial reduction in earnings at a time when many have reached or about to reach the peak of their careers. This is also demonstrated by a unique feature of becoming a judge at the level of District Court and above: the undertaking given not to return to practice after ceasing to be a judge. I know of no other profession in which such a restriction occurs. It means that in reality, a legal practitioner who becomes a judge will not be able to return to the very profession he or she was trained for and has spent many years in developing. This puts into proper perspective the significance of joining the Judiciary.

In order to address some of the difficulties in recruitment particularly at the level of the Court of First Instance, I am glad to see that the Government has agreed to a package of proposals enhancing the salary as well as the terms and conditions of service of judges. The Government has done so after recommendations made by the Standing Committee on Judicial Salaries and Conditions of Service. Both the Government and Standing Committee have consistently supported the needs of the Judiciary over the years. I am extremely grateful for this support. The package of proposals will in due course be considered by the Legislative Council.

The society in which we all live and work is a complex one. The complexities are reflected in the nature of the legal disputes that go before the courts for resolution. Some of these disputes I have referred to as high profile and may involve important political, economic or social consequences. This should, I reiterate, be seen in proper light. The courts deal with these types of case in precisely the same way as any other case: strictly in accordance with the law and legal principle. Our judges, whom you see every year in the Opening of the Legal Year, are answerable to the community in which they serve and I can assure everyone in the community that each of them will continue to discharge without compromise their constitutional duty and responsibilities.

It only remains for me to wish you and your families good health, happiness and fulfilment in 2017 and in the Year of the Rooster. Thank you.

Ends/Monday, January 9, 2017

Issued at HKT 20:03

Issued at HKT 20:03

NNNN